Restless : Forging Ahead

In 1930, Keyes turned forty-five years of age. She had traveled around the world and more travels were ahead of her. She had met deadline after deadline for Good Housekeeping and, after resigning her position there, took on a monthly column called “Pine Cones” for Yankee magazine. She continued doing research for her novels and broadened the scope of her writings to include Catholic history. She sought and found new publishing opportunities and her fiction and nonfiction appeared in a range of magazines in the 1930s: Delineator, Writer’s Year Book, Canadian Home Journal, Junior Home, the Cunarder, Home Magazine, Foreign Travel, St. Nicholas, and Travel. She worked out arrangements to have her new novels run as magazine serials and she found foreign publishers who issued her books. She was always working.

In the period between 1931 and 1939, Keyes also faced great personal changes in her life. Within two years of the decade’s end, Keyes lost both her husband and her mother. Her adult sons began independent lives, became self-supporting, and married. As Keyes’s sphere of responsibility grew smaller, she was afforded greater opportunity for self-determination. This transformative period would also see Keyes’s conversion to Catholicism and the authoring of more books of a religious focus. With greater liberty to make choices independent of other’s needs, Keyes devoted more time to her writing as she entered the phase of her life for which she is most remembered. This evolution would not have been possible without the changes in her private life and the professional strides she made during the 1930s.

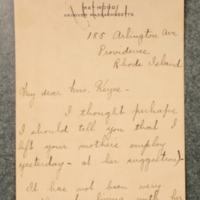

In 1932, Keyes received a letter from her mother Louise’s housekeeper in Newbury, Vermont, explaining why she was leaving her mother’s employ. Louise was then over eighty years old and her husband William Taisey was about forty years of age. Alice Manley told Keyes that conditions had not been pleasant in the household since “the boy stopped visiting her.” Letters between daughter and mother reflect the coolness of their relationship in these years. Louise Fuller Johnson Underhill Wheeler Pillsbury Taisey died in October 1939. Within the month, Louise’s widowed husband remarried.

Harry Keyes died in North Haverhill on June 19, 1938. Their relationship had cooled more than twenty years earlier when her husband dismissed “sex from his personal life.” [1] Harry seems to have never accepted his wife’s writing life. His silences and “gloomy attitude” at home made Keyes “disheartened and unhappy” and she turned to friends to fill the void in her life. In the 1930s and beyond, women friends helped Keyes not only by providing friendly companionship but also by supporting her in times of need. For example, in 1934, Keyes turned to one of her former Beehive friends, Genevieve Gudger, for both moral and financial support after a serious car accident requiring a long convalescence strained the family’s finances. Gudger lent Keyes $2,000 to meet her expenses and, although Keyes was eventually paid a settlement in the amount of $2,615, she had difficulty in repaying her debt to Gudger.

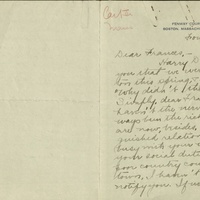

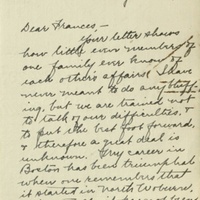

Outwardly, the Keyes family and its fortunes seemed secure if not excellent. When Carter Morris, the Director of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, visited Washington with his wife Beatrice in 1933, he failed to call on Keyes, later writing that he did not want to bother “his distinguished relative.” Keyes told Morris that she hoped that next time he was in town she would not hear about it after the fact and that he would arrange to see her. In response, Morris candidly explained that experiences in Boston had made him wary of accepting invitations from wealthy individuals, including Mrs. Gardner, because the issuer then expected an invitation in return. Correspondence indicates that he saw himself as the poor cousin of the wealthy Frances Parkinson Keyes and she did not dissuade him of this idea.

Notes:

1) All Flags Flying, 80. ↵

Related Documents: